Larry Summers has a very good piece today in the FT on the irrationality of raising rates and the limits of monetary policy in the current environment. I largely agree with his views as I hashed out in September. But the Summers piece got me thinking about the precise limits of Fed policy here. Summers says the limit is about 100 bps. I think he’s probably pretty darn close.

Historically, the economy does not perform well in an environment in which the yield curve inverts. This makes sense because the credit markets tighten up in an environment in which it is more expensive to borrow short than lend long. This is one reason why Central Bank policy can be very effective during a tightening phase. The Central Bank can close the credit pipes very quickly if it so desires by making it unprofitable to be a bank. I’ve never understood why Central Banks willingly invert yield curves, but they do and it almost always leads to a bad outcome.

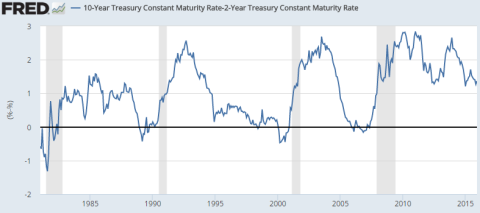

If we look at the current yield curve the Fed has very little wriggle room:

The hope, of course, is that by raising short rates the Fed will be front running a stronger economy and rising long rates. There are some signs that inflation could come out of hiding in the next 18 months, but I would be very surprised if we saw a substantial increase in long rates in the coming couple of years just because there are too many disinflationary macro headwinds. This means that the Fed is likely looking at a flat or flatter yield curve in the future. They have about 125 bps of wriggle room at present before they invert the yield curve.

This means the risk/reward of a Fed tightening are very low at this point in the business cycle. If they tighten too much too fast the credit markets will likely slow even further than they already have. This will be explicit and dangerous tightening of policy. The Fed is hoping the long end of the curve reacts to stronger economic growth, potentially rising inflation and higher demand for credit. And while I am not necessarily bearish about growth prospects in the coming 18 months I do think we’re unnecessarily trying to thread the needle with a rate hike here. The Fed has very little room for error. They should proceed with extreme caution.

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.