One of the more valuable understandings in macroeconomics is the fallacy of composition. For instance, the government sector is an aggregated sector like the household sector. Households, individually, can “run out of money”, but the household sector in aggregate can’t “run out of money”. Similarly, the government sector cannot, in aggregate, run out of money. They are, as I like to say, “contingent currency issuers”, both of whom can create money (banks create money in the private sector and the government can literally print money in the public sector). One clear conclusion from this is that the government doesn’t have a solvency constraint like an individual household does (except in highly unusual circumstances like foreign denominated debts).

The reasonable response to this is that the government can’t default because it can print money, but it can print money and cause high inflation and inflation is similar to default. This is true, but let’s parse this out because the cause and effect is important.

We reside in a credit based monetary system. That means almost all of the money in our system exists as a result of a simple accounting relationship. Let’s say you have a great idea for a new technology that you think everyone will love and you think this technology will improve living standards. But you don’t have the funding to produce and market the new technology so you go to your local bank to take on a loan. You have excellent credit and maybe even some collateral so the bank is happy to extend you some credit. In doing so the bank creates a loan which creates a deposit for you to go out and spend.

What’s happened here? The money supply has increased. And so has your purchasing power. And you use that purchasing power to go out and build your new technology and sell it. Let’s assume that after a few years of this your technology is a big success, has made many lives better, improved productivity for others and increased the amount of other goods and services your labor hours can currently purchase. In other words, society is better off because of your technology despite the increase in the money supply and the inevitable inflation that will likely accompany this.

The key is understanding the simple point that enhancements in productivity allow us to consume and produce more goods and service with the same number of labor hours! Said differently, your living standards improve despite an increase in inflation.

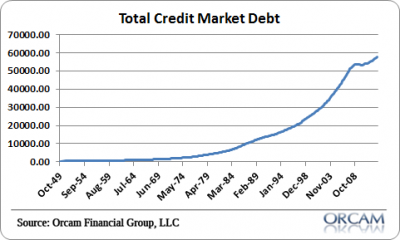

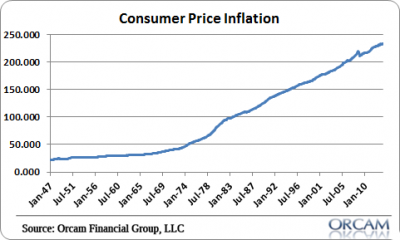

The US economy over the last 100+ years is basically one big example of this relationship between credit, inflation and output. Here are some long-term charts displaying what was essentially described above:

In a credit based monetary system credit IS money. And the supply of credit will expand over time as the economy grows to support a larger credit base. Yes, at times this system will inevitably become unstable because its participants will take on more credit than they can afford or make other irrational decisions that cause imbalances, but over the long-term the economy is basically one big credit creating productivity enhancing machine that pretty much ALWAYS has higher inflation, higher credit levels AND, most importantly, increased productivity and output.

Further, a modestly positive rate of inflation is perfectly normal in a credit based system for four primary reasons:

- Prices are sticky. This is the theory that prices tend to have upward momentum. For example, you want your wage to increase every year because you presumably become more productive at your expertise. This puts upward pressure on the price level because you are constantly demanding a higher wage. Further, prices (and especially wages) tend to exhibit upward rigidity. That is, even when the economy slows or enters a recession wages tend not to decline. This sticky price factor puts a persistent upward pressure on the overall price level.

- Governments cause inflation. Governments create money and in doing so they can put upward pressure on prices. But governments don’t always engage in positive net present value endeavors. For example, defending the country during a war has a negative net present value in economic terms. You are building things only to blow them up all the while reducing the size of your workforce due to death. This isn’t the most economically efficient thing to do and that’s just one example of what governments often engage in. The entire operations of a government could be said to have a negative net present value in economic terms – operating the regulatory regime, courts, military, fire department, etc. These things have a negative net present economic value, but a very positive net present social value. So you could argue that a lot of government spending puts upward pressure on the price level because it’s essentially the price we pay for having rules, regulations, military, etc.

- Businesses aren’t always efficient. 9 out of 10 businesses fail over the course of their life. In the process of doing so they will operate inefficiently at times, perhaps most of the time. This is all part of the process of creative destruction, but it can also be an inefficient process at times as businesses waste money on endeavors that are deemed, in the long-run, to be inefficient. This can put upward pressure on the price level as more productive entities outcompete the less productive entities. In aggregate competition should keep prices low, but the process of price discovery often entails an efficient route with many failures along the way.

- Money is elastic. We reside in a credit based money system. A fixed money supply system has never worked in human history. Credit systems always grow from a fixed system for numerous reasons. And this elastic money supply means that the money supply will usually rise to meet the growing needs of the society using that money. This elasticity can be good and bad. At times it can be abused by governments or the private sector and lead to booms that result in busts. At worst, it can result in high inflation or hyperinflation. Credit based money systems are adaptive due to their elasticity and this is usually a good thing, but it doesn’t mean things can’t go very wrong with an expanding money supply.

So we need to be careful saying that inflation is another form of default because default implies worsening conditions when, in fact, living standards often rise despite some level of modest inflation. So, yes, the US Dollar has lost purchasing power over the last 100+ years, but we are all actually better off because our productivity allows us to purchase more goods and services with the same number of labor hours.

The key point is that inflation and insolvency are very different animals with very different causes. In the case of a true default the entity defaulting becomes highly unproductive to the point of not being able to service debts, whereas the aggregate economy often becomes more productive despite a modest rate of inflation.

While a moderate rate of inflation could be totally normal it is important to note that a hyperinflation is a very different situation. A hyperinflation or even a high rate of inflation is often a partial or full blown rejection of the currency and asset allocators are trading the currency in exchange for almost anything else. In this case the government has effectively run out of willing holders of its liabilities. And although the government will not likely default on itself it does have difficulty finding willing private sector holders of its liabilities. Though this is not a technical bankruptcy in nominal terms it is essentially a bankruptcy in real terms.

When considering this scenario it’s important to understand a crucial point – hyperinflation has many causes that are generally different from an insolvency. Remember, a currency issuer with its own central bank is not going to “run out of money” because it has its own bank which can print money. An insolvency is when a debtor runs out of money. The government doesn’t run out of money during a hyperinflation, but it can run out of private sector holders of its liabilities. While it’s commonly believed that this results from “printing money” the reality is that printing money is usually the result of other exogenous forces including:

- Collapse in production.

- Rampant government corruption.

- Loss of a war.

- Regime change or regime collapse.

- Loss of monetary sovereignty generally via a pegged currency or foreign denominated debt.

- Loss of monetary sovereignty due to collapse in private sector production.

I want to emphasize that a hyperinflation can have different causes than an insolvency so they are similar, but different diseases. As a general rule it is safe to argue that a hyperinflation generally occurs when the government prints money in response to an exogenous event that resulted in a production collapse. In this case the aggregate economy has reduced demand for government credit (money) AND reduced demand for goods and services denominated in that currency. In an insolvency you have high demand for credit and a shortage in output that gives you access to credit. In other words, insolvency is a microeconomic event while hyperinflation is a macroeconomic event. So they are different but similar diseases that inflict governments in different ways than they inflict private households or businesses.

This is not to say that the government cannot cause hyperinflation. It absolutely can, but it’s important to understand what generally causes hyperinflation. While many believe it is “printing money” it is usually other exogenous factors and understanding the importance of this difference is oftentimes the mistake that people make when they confuse a government default for a household or business default. So while hyperinflation and insolvency are devastating financial events they often have different causes and in the context of government finances that is an important distinction to understand.

Please read the following pieces for some important related topics:

Understanding the causes of hyperinflation

Why Inflation is Usually Positive

Has the US Dollar Lost 99% of its Purchasing Power Since 1913?

Can a Sovereign Currency Issuer Default?

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.

Comments are closed.