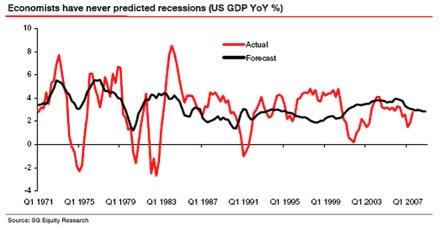

It’s become fashionable in recent years to shun all types of forecasting about the future. This narrative usually involves the cherry picking of bad forecasts to prove the point. For instance, we often hear about how economists have never predicted recessions or how Wall Street strategists never predict bear markets. Something like this might be presented as evidence of how bad these people are at forecasting the future:

(Look at how bad/good these economists are at predicting recession/expansion!)

When presented in a biased manner it does prove that economists are quite bad at predicting recessions. But what if I presented this data as evidence that ecomomists are usually optimistic and the economy rarely goes into recession? Well, by that measure it actually looks like economists are quite good at predicting expansions since economists are always optimistic and the economy is usually in expansion. The same could be said for Wall Street strategists who are almost always optimistic. The fact that they’re never bearish doesn’t mean they’re bad forecasters. In fact, it means they’re usually right since the stock market is positive about 80% of the time.

Of course, you have to keep things in the right perspective. The anti-forecasters want everyone to believe that there is some way to make decisions about the future without making forecasts. This is obviously nonsense since any decision about the future involves an implicit forecast about future outcomes. Those who shun forecasting are merely trying to confirm their own biased perspectives. The reality, as I’ve shown before, is that we shouldn’t shun forecasts. We should shun low probability forecasts. And as the evidence clearly shows, the shorter the time frame, the lower probability the forecast.

Making decisions about the future necessarily involves some framework within which we explicitly or implicitly forecast future outcomes. Whether we’re crossing the street or allocating assets we have to make a forecast about how certain things might play out and what the probability of success might be. And when it comes to the financial markets we know that having a longer time frame increases our odds of higher probability forecasts because macro trends (such as long-term profit growth and economic growth) tend to be reinforcing in the long-term.

A little forecasting is good. A little forecasting is necessary. But more important is the process by which one goes about making these forecasts. Are they short-term forecasts resulting in high fee, tax inefficient and low probability outcomes? Or are they longer-term low fee, tax efficient and high probability forecasts? Understanding the difference could be the difference between meeting your financial goals and coming up woefully short.

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.