One of the nice things about thinking of the world in macro terms is that you are less inclined to fall victim to a fallacy of composition. That is, in the financial world we tend not to think in terms of aggregates so we often extrapolate personal or localized experiences into broader concepts which often results in mistakes. The most common economic fallacy of composition is thinking that if you save more then you’re better off therefore everyone else should save more. This obviously can’t be true at the aggregate level because if everyone saved more then everyone would have less income. Likewise, in “the markets” we often think of “the market” as being something like the S&P 500 (or worse, the Dow 30) when the reality is that the “stock market” is a global market that is much broader than the S&P 500. And the financial markets are much broader than the stock markets.

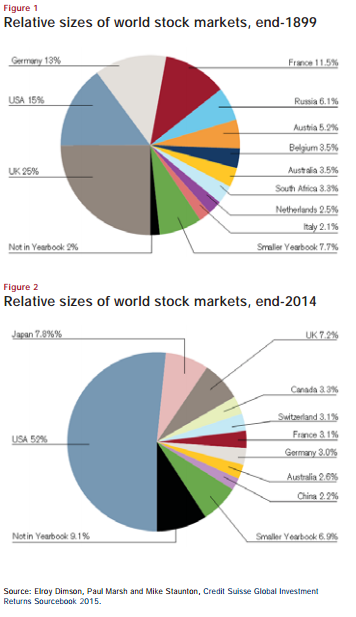

I got to thinking about all of this as I was going through the Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook (see here). They had this fabulous chart of the dynamism of the global equity market over the last 100+ years:

This chart is interesting because it shows a number of things. First, the USA was once a relatively small slice of the total market cap of outstanding stocks. Second, the reason the USA has performed so well over the last 100 years is, in large part, the result of a massive capture of market share by US corporations.

This has huge implications for portfolios going forward. There is, in my opinion, a strong likelihood that the USA will lose market share to foreign firms as emerging markets become the growth engine of the world and the US economy matures and slows. So a slice of global equity market exposure not only makes sense for broad diversification, but also when considering a strategic allocation towards potentially higher growth regions.

This image also shows how important it is to be dynamic and forward looking in your portfolio to some degree. John Bogle recently made headlines for stating that a US investor shouldn’t be invested abroad. I’d be willing to bet if Bogle had been in the UK in 1899 talking about his portfolio preferences, he would have said a UK investor should stay fully invested in the UK. Why even bother investing in an emerging market like the USA? I am sure that investing in the USA back then looked fairly silly to a foreign investor. That was obviously a huge mistake.

The point is, the future composition of the outstanding mix of global financial assets will change and investors who shun forecasting and some degree of necessary dynamism in their portfolios are very likely to generate returns that will be based on recency bias and extrapolative expectations (expecting the future to look like the past). One of the big lessons from history is that the future rhymes, but it rarely repeats. And a little bit of intelligent forecasting about what the future might look like could go a long way to helping your portfolio in the future.

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.