Economists all over the place are up in arms over a recent NY Times blog piece by Casey Mulligan which essentially says that monetary policy stinks and has no impact on the economy. Mulligan says:

“New research confirms that the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy has little effect on a number of financial markets, let alone the wider economy. Politicians, and a few economists, have been imploring the Federal Reserve to help the economy grow before November. But the effects of monetary policy on the wider economy are small.”

That didn’t go over so well, with, oh, just about every economist who writes a prominent website these days. Brad Delong says:

“This is really embarrassing, New York Times: really, really embarrassing.

The first joke comes in Casey Mulligan’s first paragraph: the Fed does not lend money to banks on an overnight basis at the Federal Funds Rate. The Fed lends money to banks at an interest rate called the Discount Rate. The Federal Funds rate is the rate at which banks lend their Federal Funds–the deposits they have at the Federal Reserve–to each other. That’s why it is called the Federal Funds rate.”

Paul Krugman says:

“Mulligan tries to refute people like, well, me, who say that the zero lower bound makes the case for fiscal policy. My argument is that when you’re up against the ZLB (OK, it’s more a minus 0.1 percent bound, but no significant difference), conventional monetary policy is ineffective, so you need other tools.

And Mulligan’s answer is that this is foolish, because monetary policy is nevereffective. Huh?”

Scott Sumner says:

“Let’s start with the fact that everyone who works in the financial markets thinks this is nonsense. Of course they also think the EMH is nonsense, and it’s true . . . er . . . truish. But this time they are right. Here’s the market response to the Fed’s unexpectedly large rate cut of January 3, 2001:

(insert chart that I am too lazy to upload with crazy market reaction to FOMC decision).

Since I have an opinion and all I figure I might as well chime in as well to express my displeasure with extreme statements – given my loathing of extreme position taking!

1) Monetary policy has the potential to be incredibly powerful – even in a balance sheet recession (or a liquidity trap or a excess money demand environment depending your choice of economic approach). The Federal Reserve has a bottomless supply of reserves that it can tap to enact policy. If they wanted to pin the entire treasury curve at 0% they could. That’s right, if they wanted to QE every government bond out of the secondary market they would inform the NY Fed to say:

“Dear Bond Markets, we are going to be purchasing all US government debt at a rate of 0%. We would like to invite you to this profit losing party. But in the interest of full disclosure (Ron Paul is on our ass like white on rice!) we would like to inform you that we have endless supply of reserves and should you try to drive the rates higher your chances of success are approximately 0%. Good day and we hope to see you there!”

The rates on government bonds would drop to 0%. Probably without the Fed even having to implement a trade….

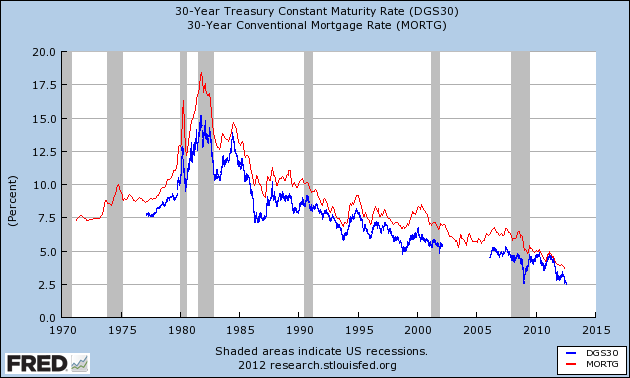

I am feeling particularly lazy right now so I am not going to run a data analysis on the correlation between government bonds and the 30 year mortgage, but here’s the correlation in chart form and a basic generalization to clarify my thinking. I think we can all agree that the Fed setting rates at 0% at the 30 year t-bond would trickle through to the 30 year mortgage rate in a way that would drive the cost of financing a home purchase (the US consumer’s largest asset and 73% of all debt outstanding) to a very low rate (yes, even lower than today’s very low rates).

There are other options for the Fed at this juncture, but I cherry pick that one just for ease of argument given the size of the mortgage market, its impact on the consumer and the extremeness of the policy. I think it’s beyond silly to argue that the $19 trillion in household real estate assets would not be impacted by this dramatic change or that it wouldn’t filter through the economy and other debt products in various ways. Through refinancings and the added affordability of housing I venture to argue that this would at least have SOME impact on the economy. Some of the economists mentioned above have even told me via email that they fear this might cause hyperinflation. I wouldn’t go that far, but it would certainly increase the demand for debt since it would nearly transform long-term credit into a perfect substitute for cash. I think that goes without saying. And at the end of the day, that’s how monetary policy works. By increasing or decreasing the demand for what Monetary Realism calls “inside money” or bank money.

2) Banking is a business of spreads. Banks lend at a spread over a benchmark wholesale funding cost. When the benchmark rate declines banks are then able to maintain a spread while inducing demand via lower rates. This is why you see a strong correlation between rates like the FFR and the 30 year mortgage (see chart below). Banking is ultimately a demand driven business. Loans don’t fly out the doors of banks as the money multiplier leads us to believe. So when a bank can maintain this spread and still induce stronger demand they’re driven by a strong profit motive to make loans at lower rates. In this regard, the Fed has always played a powerful role in the economy. Since most of the money in the economy is “inside money” (or bank money) it’s rather obvious that changing the cost of this money has an impact and can, at times, have an enormous effect. To claim otherwise is to misunderstand the fact that “inside money” is THE prominent form of money in the economy.

Conclusion – monetary policy has been very weak in the current environment for several reasons. The primary reason is due to a lack of demand for debt. Consumers are saddled with excessive debt so demand for “inside money” has been abnormally weak in recent years. This is perfectly normal following a credit driven bubble. And since monetary policy primarily works through altering the cost of “inside money” it’s not surprising that the actions of the Fed have appeared rather ineffective in recent years. But this unusual environment should not be taken to mean that the Fed has zero options or that monetary policy is never effective. To do so would be a vast misunderstanding of the basics of banking and the way our monetary system works. Monetary policy might be a blunt instrument at times, but let’s not make extreme comments that sound ideological or take the uniqueness of today’s environment to make sweeping generalizations.

Lastly, as I like to say, banks are the oil in the “machine” that is the monetary system. The Fed can alter the banking system in powerful ways. As the recent LIBOR scandal showed, central banks are always in the business of using banks to manipulate interest rates (that’s how they implement policy). In the USA, the Primary Dealers are the Fed’s agents for policy implementation. That’s just how it is. In recent years I have preferred other, more direct policy tools (primarily because I thought monetary policy would prove ineffective because of a lack of demand for credit), but I think it’s an exaggeration to claim “the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy has little effect on a number of financial markets, let alone the wider economy.” This doesn’t mean the Fed’s policies have a direct correlation with consumer spending or can magically transform the economy into something the Fed wants it to be, but let’s not be extreme in our conversation here. The Fed’s an incredibly powerful entity. My brief and incomplete analysis doesn’t prove that overwhelmingly, but market participants understand this. After all, “don’t fight the Fed” isn’t plastered all over Wall Street trading floors just for the fun of having slogans to read.

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.

Comments are closed.