Greg Ip, Chief Economics Commentator at the WSJ, recently had some thoughtful comments on the national debt:

“There are at least two reasons [the growing debt] matters. First, when the next recession hits, the U.S. may want to open the fiscal taps but instead have to do the opposite as tax collections sink and deficits mount. Second, while markets and the Federal Reserve both doubt interest rates will go much above 3% for the foreseeable future, the U.S. is acutely vulnerable if that is wrong because the debt is so large and so much of it comes due each year, and would have to be refinanced at higher rates.”

Ip covers a lot of ground in this piece and offers a pretty balanced view. I think he’s right not to be too blase about the national debt. Governments can wreck an economy faster than many think, but I think these arguments about the USA are generally based on false understandings and exaggerations in the severity of the problems. Let’s talk about Ip’s worries in a bit more detail.

Does the USA Have Policy Flexibility in an Economic Downturn?

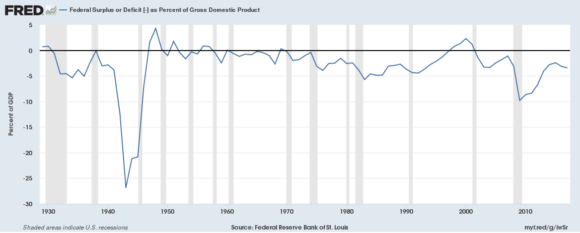

This has become a common concern in recent years as the Fed has expanded its balance sheet and cut rates and deficits have remained moderately high. The concern is that the USA has no policy ammunition left. This might be true on the Fed’s side, but it is less so on the Treasury’s side. After all, the deficit is just 3.5% of GDP as of now. It ballooned to over 10% of GDP during the crisis and was as high as 27% during the 1940s.

We know that a deficit of 10% of GDP didn’t cause high inflation in 2009 so it’s safe to assume we have quite a bit of policy flexibility here. If the US economy were to enter a recession the deficit would naturally expand to some degree as tax receipts decline and spending increases automatically, but there’s no reason to think that we wouldn’t have some flexibility to expand the deficit with some discretion as well.

Is the USA “Acutely Vulnerable” To Higher Interest Rates?

As I explained a few weeks ago, the interest expenses on the national debt do not pose an unusual threat to the budget:

“the average weighted maturity of the national debt is way below what a 5% Bond would be the equivalent of. As of the end of last year the average weighted maturity of the public debt was about 5.8 years. That was about 1.2% last year or about $265B. With rates having jumped this figure is closer to about a 2.8% interest rate or about $410B per year.

So let’s assume rates jump to an average that would result in the equivalent of a 5% rate on the public debt. In that case we’d end up paying about $733B in annual interest. To put this in perspective, that would be about 17% of current federal expenditures. That would be a big jump from where we are, but not much higher than where this level was for most of the 1980s and 1990s.”

I don’t see the big fuss here. The USA didn’t go bankrupt or have trouble financing the national debt in the 80’s and 90’s so why would a surge in interest expenses be any different this time?

NB – All of this assumes that the USA has to raise the average maturity of its debt and hence the interest costs. As I’ve argued in the past, this isn’t necessarily true.

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.