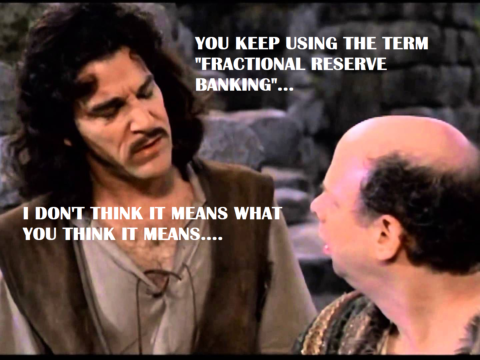

The term “fractional reserve banking” is commonly used in a confusing manner in both mainstream economics and within lay conversations about economics. I hope this article will clear up some of the common confusions.

of the common confusions.

Fractional reserve banking is the idea that banks take their reserves and lend them into some fraction based on the quantity of reserves they hold. This idea has been largely debunked since the financial crisis. In reality, banks do not lend their reserves, except to one another inside of the reserve system (which is a closed system, ie, reserves don’t even leave the system). They don’t even lend based on the quantity of reserves they hold. In reality, banks make loans and find reserves after the fact if they must. And if the Central Bank has a reserve requirement in place then the Central Bank will have to supply the quantity of reserves necessary to allow banks to meet the regulations they create.¹

This blows up most of the narratives that commonly circulate which imply that the Central Bank controls the money supply and all that. In reality, the US Treasury is the entity that mostly prints net financial assets and the Federal Reserve, via programs like QE, just changes the composition of those assets after the fact by buying assets (which involves creating new reserves and removing a T-Bond from the private sector).

But this doesn’t mean that our economy isn’t “fractionally reserved” in any sense. Yes, it’s incorrect to say that the Central Bank has some sort of strict control of the money supply via reserves. But out economy is still fractionally reserved in the sense that investment constrains how much money we can realistically create. rather than calling it a fractional reserve system it’s more accurate to say that it’s a fractional wealth system since we are really leveraging our existing wealth to create new financial assets/liabilities/wealth.

So, think of it like this – if I want to build a house I can borrow $100,000 from a local bank. That bank might agree to make the loan by requiring me to post some other assets as collateral. In this case let’s just pretend I have a business that’s worth $100,000. So, the bank agrees to create $100,000 of brand spanking new money. It didn’t come from anywhere. It’s not like they took in $100,000 of deposits and loaned those out.² They didn’t take $100,000 of reserves to lend to me. They literally just expand their balance sheet and we have a new endogenous contract for $100,000. It’s a lot like cell division. Yes, the cells divide and create new cells, but the new cells are endogenous in the sense that, even though they come from the existing cells, they are new in and of themselves.

Of course, this is all leveraged in a certain sense. The bank is leveraging their capital position. After all, they aren’t even allowed to make loans if they can’t meet certain capital requirements. And the new loan is leveraged from the collateral I post. In essence, the wealth we create in the past allows us to leverage that wealth to create more wealth in the future. So, I’ve created a company that I post as collateral. And the bank has earned some profits in the past that they retain as capital. And together we’ve entered into a new contract to create a new loan that will allow me to buy the goods to build a new house. And when that house is built we will have even more real assets that can potentially be posted as collateral.

This is basically how the entire economy works in the long-run. And it’s why debt (and assets and net worth) virtually always increase in the long-run. So, yes, there is a certain sense in which we fractionally reserve our entire financial system to create more assets/liabilities/wealth in the long-run. But the idea that the Central Bank is somehow at the center of all of this is misleading at best. Banks might fractionally leverage their balance sheets, but reserves are just one asset that banks hold among many that make that process sustainable.

¹ – This doesn’t mean that banks don’t need reserves to make loans or that the Central Bank can’t constrain the banking system in meaningful ways. It just means that banks make loans and find reserves after the fact and the Central Bank will always supply reserves to banks that it deems healthy. Therefore, reserves don’t constrain bank lending in the sense that some textbooks imply.

² – The idea that loans create deposits should not be misconstrued to mean that banks do not need deposits to manage their balance sheets. It is clearer to say that a bank manages its assets and liabilities in such a way that their assets contribute positively to their net asset/liability position. In doing so, deposits “fund” loans to the extent that they help the bank better leverage their operation into future loans and capital. In other words, banks want/need deposits because they’re a very inexpensive liability for them to hold. For more reading on this please see “Loans Create Deposits in Context”.

References

1 – Inside Money and Outside Money, Lagos R. 2006.

2 – Repeat After Me: Banks Cannot And Do Not “Lend Out” Reserves, Standard and Poors, 2013

3- Money, Reserves, and the Transmission of Monetary Policy: Does the Money Multiplier Exist?, Federal Reserve, 2012

4 – Banks are not intermediaries of loanable funds — and why this matters, Bank of England, 2015

5 – Understanding the Modern Monetary System, Roche C. 2011.

6- The Basics of Banking, Roche C. 2014

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.