A little over a year ago, I ran some of the unfortunate math behind our economic plight. I said:

“the initial stimulus plan helped give the appearance of recovery, but it did not solve the actual problem. It merely papered over the problems and injected some short-term relief. The problem of debt was still (and still is) brewing under the surface. Now as the stimulus effect wears off we are realizing that the household sector remains incredibly weak, but there is no political will to attempt to solve the problems at hand.

…What this all likely means is that growth will remain well below trend as the consumer continues to de-leverage. This creates a particularly uncertain environment for corporations and leaves the economy highly susceptible to exogenous risks (China, European debt crisis, housing double dip, etc). Political gridlock and continued misdiagnosis in government will certainly not help.”

My thinking was relatively simple – the balance sheet recession was putting unusual downside pressure on consumer spending and the paper recovery due to government deficits was slowly peeling away, but the deficit remained large enough to avoid any sort of collapse. Since then, the U.S. economy has weakened, but not collapsed. In other words, the balance sheet recession (BSR) has persisted, but so has the government aid to a large degree.

Can the Balance Sheet Recession be modeled?

I’ve been working on trying to build an economic model that would accurately reflect my work on the balance sheet recession. When I was building the model I expected the historical data to be a poor reflection of the general economic conditions of the last 50 years, but the results surprised me.

What I’ve built here is a model for future expected GDP growth using a combination of the sectoral balances approach along with a private sector credit element. My goal was to capture the story that has been ravaging the U.S. economy for the last few years. For those who aren’t aware of the balance sheet recession – it is essentially what occurs following an era of private sector credit accumulation resulting in a boom/bust phase. The asset price correction leaves the debtors servicing pre-bubble era debts with post bubble era cash flows. The result is a rare reallocation of spending to saving as the spenders focus on paying down their debts.

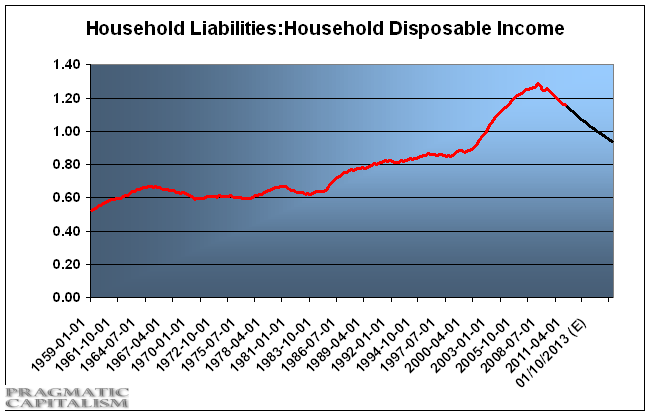

This has always been a sustainable and self correcting process over the years because the U.S. consumer has always been below the threshold of unsustainable debt:income levels and the U.S. government has generally run deficits that exceeded minimum required levels, thus providing a natural stabilizing element. That all changed with this most recent recession when household debt to income levels ballooned to over 125%.

Some economists have called the BSR theory “inadequate”, but I have argued that these economists are working under a defunct economic model that misunderstands the important difference between certain creditors and debtors within the economy. They claim that “for every creditor there is a debtor”, but fail to understand that all debtors and creditors are not created equal. More recently, they have claimed that the household balance sheet position is not as bad as the BSR theorists claim. I think the evidence points to the contrary as consumer borrowing has experienced a once in a generation collapse.

Anyhow, there are lots of moving parts in these inputs for the model (current account estimates, CPI estimates, etc) and it’s still very much a work in progress that I hope to have completed some time next year, but what I’ve built is a fairly simple preliminary model which attempts to predict economic growth based on private credit expansion and an understanding of the importance of the sectoral balances and the ways that the three sectors of the economy interact. The math behind the model essentially shows contracting horizontal money and insufficient vertical money creation to bring the economy back to anything resembling healthy growth. I fully understand that trying to model so many moving parts is an imprecise exercise to some degree, but I think we can acquire a better understanding of the likely path of the U.S. economy using this data. *

I’ve assumed a relatively consistent current account deficit (3.5%) and utilized the CBO’s 2012 and 2013 estimates for government deficits (roughly 8.6% and 4.5% of GDP). I’ve also assumed that private sector credit growth will moderately improve over the coming two years from a negative position to a neutral position (one could easily argue that this is optimistic, but I am erring on the side of reduced government deficits resulting in less debt reduction than is currently necessary). The math does not lead to a rosy outlook for the coming years and even given some margin of error, the odds of strong economic growth are low at best.

What are the findings of this model?

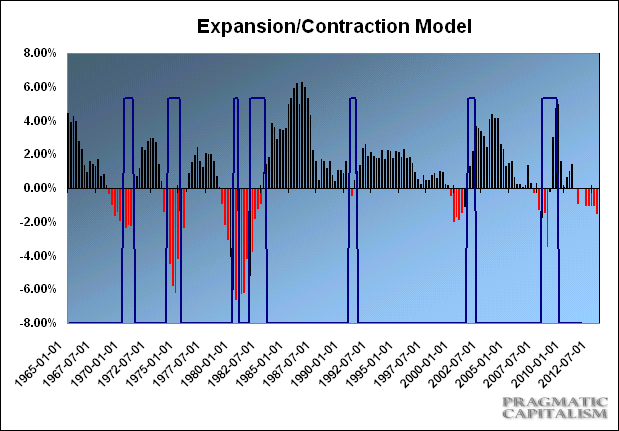

The output from this model shows a rather stunning lead time over the last 7 recessions (to my surprise, it appears that our current predicament is not quite as unique as one might originally believe – it is only far larger). The model leads every recession by several quarters with the exception of the early 90’s recession which was shallow by any metric.

The current data does not bode well for the U.S. economy. Based on this model, the U.S. economy is likely to begin officially contracting in 2012 as the balance sheet recession continues and government spending slows. The good news is that the model is not predicting a contraction that is deep like we saw in the tumultuous 70’s. The bad news is that our government does not understand that we have been in one long balance sheet recession this entire time and as private sector credit growth continues contracting (or flatlining), they will be required to offset the lack of growth via higher than normal budget deficits. You can see that the current recession was well on its way to becoming a disaster like the 70’s until Q1 2009 when the deficits exploded. The problem currently, is that the Federal budget deficit is likely to remain high in 2012, but then peel off to a level of 4.5% of GDP in 2013 (again using CBO estimates and assuming no further stimulus of any kind). That’s worrisome as I have estimated that the BSR will persist into 2013 without a surprise resurgence in private sector credit (which will be unsustainable anyhow).

(Contractions highlighted in red, recessions in blue areas)

The bottom line is that this model is showing an economy likely to begin moderately contracting in 2012 (~0.88%) although I would argue that we’re splitting hairs talking about the difference between real growth and real contraction when the economy is as weak as it is. The truth is, we’re in a balance sheet recession and as the government slowly peels away the spending that has propped up the U.S. economy, the consumer will prove weak once again. So, the bad news is we’re still in for a muddle through period. The good news is the deficit will remain large enough to avoid substantial economic contraction. But the worst news is that our government and the world’s leading economists still have no idea what is causing the current malaise so the risks in this environment remain far higher than they should be.

* The upside risks to this outlook are a vast improvement in private sector credit expansion and/or a sizable increase in the government’s budget deficit. The downside risks are all exogenous in my opinion – China, Europe, continued BRIC slow-down, cost push inflation via oil or other commodities, etc.

** This is not an economic forecast, but rather a new model I am still in the process of working on.

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.

Comments are closed.