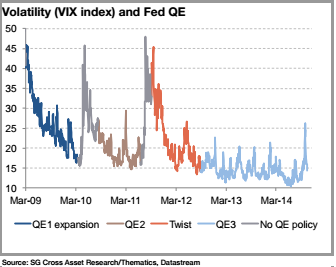

The following chart from a recent Societe Generale research piece really jumped out at me. It shows the Volatility Index during the various iterations of QE. And if one were to just eye ball this you might conclude that QE smoothed the stock market’s gyrations by a good deal. That is, the S&P 500 was generally less volatile when QE was in place.

Why does that matter? Well, from an accounting perspective, the holy grail of Central Planning would be the creation of perfectly smooth balance sheet and income statement patterns. If you could create an environment with almost no variation in spending then you could theoretically eliminate the business cycle which means you’d eliminate all downside deviations in the economy. That is, of course, a totally unrealistic goal, but we can theorize nonetheless.

Now, stock markets play a huge role in people’s balance sheets as a key component of saving. And since spending is a function of income relative to desired saving then stabilizing that saving variable could go a long way towards smoothing the business cycle. And if QE contributes to smoothing some component of this whole equation then that would be an obvious positive.

I went back and crunched some numbers here and the findings are interesting. Historically, the stock market is actually very boring on any day-to-day basis. It averages just a 0.03% move on a daily basis going back to 1950 with a standard deviation of 1% on a day-to-day basis. So it’s positive, but just marginally. But when we look at the various iterations of QE we see a shift. The volatility increases marginally with QE1 (mainly because the Fed’s balance sheet started to increase before the crash), but the average daily return of the S&P 500 jumps to 0.12%. When QE2 is initiated the volatility drops with the standard deviation of the daily returns falling to 0.79% and the average daily return falling to 0.04%. And with QE3 the standard deviation of the daily moves remains well below the historical average at 0.88% with an average upside change of 0.07%.

Interestingly, in the periods (during the last 6 years) when there was no QE the average daily return drops to 0.02% with a standard deviation of 1.3%. So the market became more volatile with a lower average return. That would imply that the market’s were much less stable without QE.

Now, none of this is really that shocking to anyone who’s been paying attention to the markets over the last 5 years. There has been a “relentless bid” under the market that has been attributed to QE at least to some degree. Of course, there’s no way of really knowing if this can actually be attributed to the Fed or not, but this data would seem to imply that there has been some smoothing of an important balance sheet component. I’ve argued that QE played a smaller role in the market rally and the economy than most presume. But there’s also no serious negative shock by which we can judge the efficacy of this sort of policy.

Asset price increases are an obvious positive for the economy so long as they are sustainable. That is, as long as the underlying fundamentals of the market justify current prices and future expectations then asset price increases contribute to net worth and balance sheet stability in a positive way. But negative volatility can also contribute negatively to the economy when balance sheets deteriorate and consumers become less certain about the financial stability. But negative volatility is often the result of positive volatility.

As Hyman Minsky once noted, stability creates instability. And so a Central Bank that is potentially putting a floor under asset prices has to be aware of the potential that irrational market participants could bid up assets higher than they can be sustained. And that would ultimately be destabilizing as it could create negative volatility in an important component of consumer balance sheets. We haven’t seen this negative potential consequence during the Fed’s balance sheet experiment, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t a potential risk that we should be mindful of. It will be interesting to see, however, if volatility in asset prices increases now that the Fed’s implicit support is gone and whether that prompts actions to initiate a new round of balance sheet expansion. And more importantly, will we eventually find out that all of this “stability” actually creates instability? I guess we won’t know until after the fact, but for now it looks like the Fed has not increased financial instability.

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.