There’s an interesting discussion going on about inflation as another form of default. Brad Delong and Noah Smith both say that Modern Monetary Theory is wrong to argue that inflation isn’t another form of default (you can read their full posts here and here). In essence, they say that the markets can dictate that a government is bankrupt even if it isn’t technically or legally bankrupt. I tend to agree with them and I’ve had some rather long and drawn out battles with the MMT people over the years about this exact topic. I remain convinced that MMT overreaches at times when emphasizing the importance of a government being able to create money and the state’s ability to attribute “value” to money. In fact, I’d argue that the MMT operational description is misleading and overemphasizes the idea that the sovereign currency issuer “spends first”. Although a sovereign currency issuer can’t be forced into a legal default, this does not mean their liabilities are always considered creditworthy.

Here’s how I think of this. Money creation is truly endogenous. We can all create money from nothing. If I go to a bank for a loan I am essentially creating a financial liability that the bank may or may not want to hold. If the bank considers me to be creditworthy they will accept my liabilities. When the loan is created the bank is holding an asset (the loan) and a liability (the deposit). Likewise, I am holding an asset (the deposit) and a liability (the loan). We tend to think of the bank as “creating” the money, but you could also think of the borrower as creating the loan. For all practical purposes, we are both willing to hold eachother’s liabilities. This is the essence of “money” creation. When someone is willing to hold your liabilities you have “credit”. And money is ultimately credit, which comes from the Latin word credere meaning to believe. But you must have credit first. Credit does not merely come from legal authority or the power of the printing press. In fact, as I’ve argued before, creditworthiness is primarily a function of output in a fiat monetary system.

The unique thing about governments is that they have their own banks and they have massive revenue sources. So they tend to have very high creditworthiness since they can tap into the output of the economy. Also, when their liabilities are denominated in a currency they can create it’s unlikely that they will encounter an environment where someone will deem them legally bankrupt. But this does not mean that their liabilities are always creditworthy or that everyone always “believes” in holding their liabilities. That is, the legal definition of being solvent does not necessarily mean their liabilities are considered valuable.

This brings me to confusion about a rather basic concept in finance that stems from the way MMT describes the world. MMT says sovereign governments don’t “fund” their spending. This is misleading. To have funding in finance means to have viable counterparties. Households fund their liabilities at the cost of inflation plus a certain amount of credit risk. Governments generally have very high levels of credibility and so they only fund their liabilities at the cost of inflation. For instance, if the US government decided not to issue bonds they could print cash and distribute it. That money has a price even though we don’t see it. That price is the cost of funding for the government.

This is a nice segue into inflation. Can’t the users of a currency reject it and essentially trade it for other currencies or assets? Of course. This is exactly what a hyperinflation is. In a hyperinflation that price is collapsing as interest rates soar. And the reason that price collapses is because the funding agents in the non-government sector are re-pricing the government’s assets lower relative to everything else. In other words, the government has fewer viable counterparties to fund their spending.

Importantly, some level of inflation is perfectly normal in a credit based monetary system because we should expect that borrowing will expand as the economy grows and improves. So inflation is not always another form of default. It is generally a healthy part of economic expansion. In addition, default might not always manifest in the form of rising bond yields or “running out of money”. This is because the sovereign currency issuer can always maintain the cost of its debt in nominal terms simply by reducing interest rates or reducing the maturity of its debts. It need not be “forced” into default by bond vigilantes. But this doesn’t mean that the market will always want to hold their liabilities. And this will usually manifest itself in the form of a foreign exchange crisis and rising inflation.

For example, if we look at Argentina since the year 2000 we can see that the Argentine Peso has actually lost an average of 18% in value relative to the US Dollar. But the rate of inflation was 11% over this period. This means that “the market” deemed the Argentine Peso to be substantially overvalued relative to potential alternatives. So, on a relative basis, the Argentinian citizens are substantially worse off in both nominal and real terms than they would be if they were using a different currency. The government might not default in legal terms, but the market’s have decided that they do not want to hold Argentinian currency at its current values which results in a devaluation that substantially reduces the standard of living for its citizens on a relative basis. Interestingly, this sort of environment can actually force a sovereign currency issuer to do things that would render it to be no longer sovereign (such as pegging the currency). So the idea of a “sovereign” currency issuer is imprecise in the first place given that this position can be dynamic in certain circumstances.*

The concept of “default” is murky considering its legal ramifications. Given a sovereign currency issuer’s unusual status in the economy, it’s better to think of this in terms of the willingness of the financial markets to hold your liabilities relative to potential alternatives. And if the financial markets don’t want to hold your liabilities then you’ve lost credibility even if you’re not legally bankrupt. The ability to create money is sometimes implied as a sort of cure all for our economic woes that can help maintain full employment and prosperity. But reality is much more complex than simply being a sovereign currency issuer. And if you agree that the government must have willing holders of its liabilities then the MMT operational description of the monetary system becomes obviously misleading as it means that the government does indeed issue liabilities to “fund” its spending.

Ultimately, the key to understanding this discussion is in understanding what it means to be “sovereign”. Sovereignty does not come merely from government mandate. Sovereignty is an economic status earned by economies who produce productive output and leverage that output into policy flexibility. We can think of governments much like corporations in the sense that they leverage the capital that their productive resources mobilize. They are solvent as long as an outside entity is willing to hold their liabilities. Governments are unusual because they establish the rules of the game and do not willingly default on themselves. But while insolvency looks different for a government we should not confuse it to mean that there is no financial constraint on a currency issuer because, by the time that insolvency is unfolding it has likely lost its sovereignty for reasons that will only be known after the fact.

Of course, it’s important to understand the difference between insolvency in financial terms and real terms. When a government is undergoing a high inflation it is insolvent in the sense that people do not want to hold the financial assets denominated in that inflating currency. Insolvency is a literal lack of money to fund spending. The cause of these episodes are quite different and many people in the mainstream media misunderstand an inflation insolvency for a financial insolvency. We would all be better served if this line of thinking was clarified so that policy could be enacted in a manner that is consistent with the true constraints of the specific economy in which those policies are being implemented.

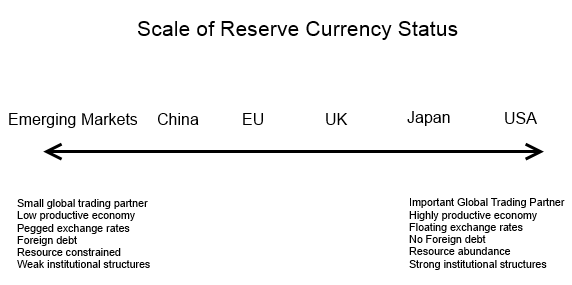

* Sovereignty is a slippery term and a concept that exists on a scale (see below for instance). Some countries have higher degrees of sovereignty than others and it can be a fleeting concept if an economy is mismanaged. I prefer the term “contingent currency issuer” to emphasize the dynamic nature of money issuance.

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.