Someone emailed the other day asking for my opinion on theories of wave cycles such as Kondratiev cycles. There are numerous different versions of this idea utilized by various market pundits and investors including Robert Precher’s Elliot Wave Theory, Harry Dent’s long wave theories and Ray Dalio’s debt cycle theories. These theories usually assume three key characteristics:

- The economy and the markets exist in a state of disequilibrium as opposed to an equilibrium or an environment in which they move from equilibrium to equilibrium.

- Bounded rationality is the dominant model and market participants are therefore limited in terms of how much information they have and how well they can process it.

- The stock and flow network of goods and services moves in long cyclical (and predictable) patterns.

This is a very appealing framework to many people because we see what looks like “cycles” in the economy and the financial markets. They ebb and flow like a sine wave. This is also an appealing model relative to most mainstream macroeconomic general equilibrium models because it doesn’t include some of the unrealistic assumptions that economists use to simplify their models (such as rational expectations or the efficient market hypothesis). In other words, this meshes with the way people actually see the world unfold before them. Unfortunately, the idea of cycles can be misleading and can generate some extremist assumptions about how the future will unfold.

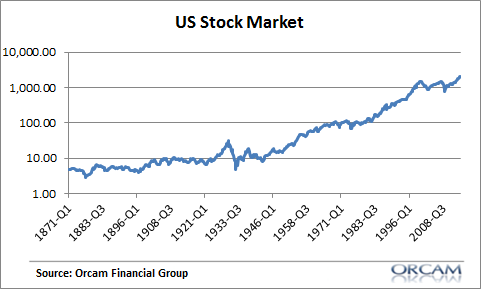

The idea of a “cycle” is very useful, but it’s important to keep these things in the proper context. We exist in a very finite time period which gives rise to recency bias and overstating the importance of seemingly significant events. So, a 10% drop in the stock market feels substantial in a 1 year period, but it is really just a normal event when viewed in a 3, 5 or 10 year time period. Further, the idea of “cycles” gives the impression that the economy and the financial markets move in big extreme waves, but the reality is that economic growth and financial market growth tends to look fairly smooth over long time periods. That is, there is a dominant boring trend in growth. Here’s a log scale of the US stock market going back to 1871:

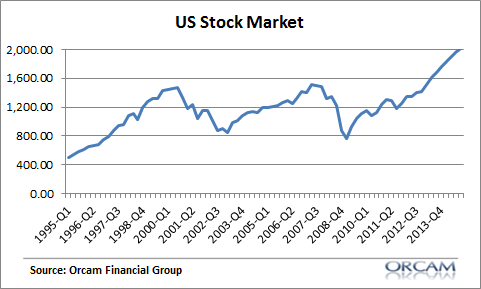

But when most people think of the financial markets and the economy they tend to think of something more like this:

This feels more like a rollercoaster and something that is highly cyclical. But if you look closely you’ll notice that the busts are much more extreme than the booms. That is, the market tends to trend then boom and then bust in a very brief period of time relative to the overall trend. With the exception of about 4 years, the last 20 years have been a fairly boring positive trend. That’s not to downplay the impact of outlier events, but the problem here is that the cyclical thinking leads people to make unrealistic temporal assumptions. For instance, how many times have we heard something like the following:

- The next crash is always right around the corner.

- Interest rates have to rise because they were high during the last cycle, now they’re low so they can only go up.

- Inflation will surge because the deflationary cycle precedes the inflationary cycle.

This sort of thinking can lead us to always think we’re in the boom OR the bust. But the world isn’t an either or environment. While the economy and financial markets have a boom/bust tendency it might not be helpful to think of the economy as always being in a state of one or the other. Rather, the economy and the financial markets tend to boom/bust/bore. Emphasis on bore because that’s the state that the economy and the financial markets tend to spend most of their time in. In other words, the economy trends for long periods of time before something triggers an irrational boom which leads to a bust before it then stabilizes and trends again.

In short, the word “cycle” can be misleading because it leads people to think in terms of something like a sine wave when the reality resembles something far less extreme. A boom/bust theory or a long wave cyclical theory of the economy and the financial markets is a fine starting point for understanding how the economy and the markets expand and contract, but the boring part of the market and economic cycle cannot be overlooked here because that is the dominant state of things during most of the “cycle”.

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.