Low interest rates have led many people to conclude that savers are being unjustly punished by a lack of interest bearing savings. In this case, we’re referring specifically to people who are trying to generate a reasonable return in a risk free or nearly risk free instrument like a Treasury Bill, CD or money market fund.¹ But this raises a more interesting question – do savers deserve a risk free rate of return?

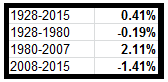

Before we can answer this question it’s helpful to put things in some historical context because the savers of recent decades have been spoiled by unusually high real returns in risk free instruments. For instance, if we look at the real returns in 3-month T-Bills we find that the 1980-2007 period stands out as an anomaly:

With the exception of the unusual period of very high and rapidly declining interest rates, savers have not traditionally generated positive real returns in T-Bills. In other words, you had to bear some substantive risk to generate a real return. This shows that many savers have probably come to expect unrealistic rates of return in risk free instruments due to this unusual 27 year period of high and declining rates.²

The theoretical question at hand is more interesting though. Should savers be entitled to a risk free return? I guess it really depends on how sustainable that savings can be. Clearly, an economy with one productive worker and one million retired savers trying to earn income cannot sustain itself as the productive output of the one worker is providing the productive output supporting the stream of income feeding the economy. In a world of high productivity and high output we can support a larger base of savers earning income from our aggregate strength in the economy. However, in a period of stagnant productivity and weak output the economy can no longer support a large base of risk free savings so the aggregate income being paid to savers must decline.

It would be nice to reside in a world where free lunches like risk free returns on our savings were a right and not something earned. But in the aggregate our ability to sustain a risk free rate of savings is a function of what we earn in the aggregate. Because we have not “earned” as much in recent years as we’d become used to earning in the 1980-2007 period we cannot afford to provide the risk free returns that we had grown accustomed to.

In a paradoxical sort of way, this is not all bad. It is, to some degree, the natural boom/bust nature of the cyclicality of growth in the economy. At present the weakness in the economy and low cost of money is begging innovators and producers to get busy and make up for the output we have lost over the years. For whatever reason that risk appetite is not taking hold. And we’ll probably have to get used to this sort of low return for savers until that improves.

¹- These instruments are all essentially the same thing (a money market fund, for instance, is comprised mainly of Treasury Bills) though we often refer to them as different things. And yes, there is nothing that is totally risk free, but for practical purposes a 3-Month T-Bill gets us about as close to that concept as possible.

² – I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that “savers” who hold nothing but risk free 3-month T-Bills are not properly allocated. And they never should have been “hurt” in the first place. A properly constructed portfolio should almost never hold nothing but 3-month T-Bills so savers who have been hurt in recent years have probably not been allocated properly. This is most likely due to irrational fears over longer maturity bonds or persistent fears over stocks.

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.