A smart reader asks how investing isn’t gambling after reading my last post. He/she says:

“While I agree with your premise that true investing is current spending for future cash flow, the only time this happens in the public markets is at an IPO. And even then, my money is still exposed to several risks of loss in ways that are similar to gambling. How do I know this company isn’t the next Enron? How do I know equities aren’t about to enter a 25+ year bear market (Japan)? How do I know whether or not Deutsche Bank isn’t about to sink the entire European banking system?”

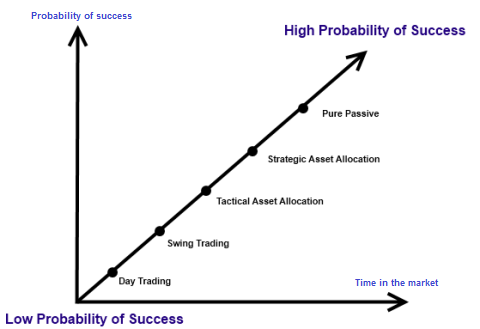

Great question.¹ The answer, in my opinion, is largely a temporal problem and relates to what I call the Intermporal Conundrum in a portfolio – the problem of time relating to someone’s risk profile. A gambler wants to get rich quick so they do things that are irrational inside of a short time period. The investor lets time work for them by applying a strategy that has a high probability of success over time. The image below might better conceptualize my thinking here:

Most of us are behaviourally biased and short-term oriented. As a result we pay high fees for “market beating” return promises, we watch financial TV too much, we log-in to see our portfolios too much, we churn up short-term capital gains, etc. This leaves many asset allocators in the bottom left hand portion of our probability of success line and unable to move towards the upper right hand portion of the line. This results in worse performance because it leads to too much market timing, higher fees and higher taxes. And we know, definitively, that these frictions erode performance and must, by definition, underperform a pure passive portfolio.²

So, how does one overcome this temporal problem? Quantifying it is a good starting point. I highlighted a nice temporal measurement tool in my new paper on portfolio construction.³ I also wrote about it a few weeks back in “How to Avoid the Problem of Short-termism“:

the allocation of savings is ultimately about asset and liability mismatch. Cash lets us protect perfectly against permanent loss risk and maintain certainty over being able to meet our short-term spending liabilities, however, because it loses purchasing power it leaves us exposed to this risk in the long-term. Cash feels safe in the short-term, but in the long-term it is the riskiest asset because it is guaranteed to decline in value relative to inflation. We can extend the duration of our financial assets to better protect against the risk of purchasing power loss, however, this increases the odds of permanent loss risk (the risk of being forced to take a loss at an inopportune time) and not having the funds when you need them.

Thinking of your savings in terms of a specific duration can be extremely helpful for overcoming the problem of short-termism. For instance, we know that cash is essentially a zero duration asset that will lose purchasing power over the long-term so if you have no temporal flexibility allocating your savings then your duration is zero and you should remain in cash. On the other hand, if you wanted to reduce your risk of purchasing power loss you could buy a bond aggregate fund which pays about 2% every year and has a duration of about 5.5 years. You might not beat the rate of inflation, but you’ll do better than cash thanks to your temporal flexibility. Of course, you need to be able to put the funds away for 5.5 years to ensure high odds that you’ll get your principal back at that time.

The stock market is what makes all of this tricky since the stock market doesn’t have a specific duration like a bond does. In the paper I used a rough heuristic technique calculating the break-even point on a range of stock market declines in an attempt to calculate the stock market’s sensitivity to price changes. I arrived at a duration of 25 years which I think is both quantitatively satisfactory and intuitively correct since the global stock market tends to have a very low probability of multi-decade bear markets.

This puts things in a nice perspective for us because it allows us to allocate our assets in a way that properly contextualizes our asset and liability mismatch problem. For instance, we can now run a simple calculation using an aggregate bond index with duration of 5.5 years and the total stock market with duration of 25 years:

PD=(S*25) + (B*5.5)

Where PD = Portfolio Duration, S = % stock allocation & B = % bond allocation.

Here’s a basic cheat sheet for thinking about this across different time periods:

By quantifying the concept of time within our portfolios we’re able to become more comfortable with the way we allocate the assets. We’re able to increase the certainty in the way we balance that asset and liability mismatch. And importantly, what this exposes is a crucial reality – when we’re dealing with stocks and bonds we’re dealing with inherently medium-term and long-term instruments which means that this rat race of short-termism is completely inconsistent with the actual structure of these instruments. After all, you’d never judge the performance of a 2 year CD inside of a 1 month period, but that’s the equivalent of what someone is doing when they judge stock market performance based on a 1 year period.

By putting the concept of duration in the proper context you can improve the odds that you won’t fall victim to the problem of short-termism. And most importantly, by being armed with this knowledge going into the asset allocation process you’ll reduce the odds of falling victim to the many behavioural biases that plague modern asset allocators. As a result, you’ll reduce your fees, reduce your tax bill and increase your average performance. But most importantly, you’ll sleep better at night.

Good portfolio management is really about conquering the problem of time. It is the struggle to match an uncertain time horizon with financial assets that have uncertain life times. But by putting things in the proper context you can improve the odds of success. In doing so, you reflect the mentality of the investor and not the mentality of the gambler.

¹ – I did not directly respond to the fears cited in this question, however, they are all temporal in nature. For instance, as I showed in a previous analysis on the importance of global asset allocation, the Japanese investor who bought a globally diversified portfolio of stocks and bonds did quite well over this time horizon even though the domestic stock market was crushed. The same basic thinking can apply to Enron and DB in Europe.

² – As you likely know from my many ramblings on this topic, pure passive is a unicorn. It exists in theory, but not in reality. As a result, most of us are forced to be active to some degree, however, there are smart ways to be active (like tax and fee efficient global asset allocation) and stupid ways to be active (like day trading).

³ – See, Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.