Here’s an excellent piece of research from Tanweer Akram of ING discussing the economics of Japan over the course of their continuing balance sheet recession.

I pulled some of the highlights from the report that I thought might look familiar. Notably, Japan’s sectoral balances and the lack of impact of monetary policy and increasing central bank balance sheets:

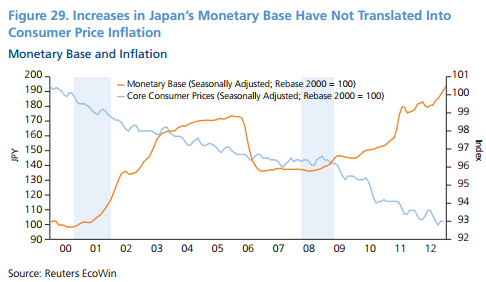

“As shown in Figure 28, the Bank of Japan’s balance sheet had been bloated even before the 2008 global recession forced central banks the world over to expand theirs. However, despite years of an expanding monetary base — and contrary to monetarist mantras — Japan remains mired in deflation (see Figures 29 and 30). Japan’s experience since the turn of the century validates the contemporary understanding of monetary policy and central banking, which holds that the expansion of central bank’s balance sheet does

not necessarily lead to higher inflation. Increases in reserves are merely outcomes of the expansion of the central bank’s balance sheet; they do not directly affect bank lending or credit growth, and inflationary pressures may not arise unless credit growth fuels economic activity. This is particularly true when an economy is characterized by excess slack and spare capacity, as Japan’s is.”

….

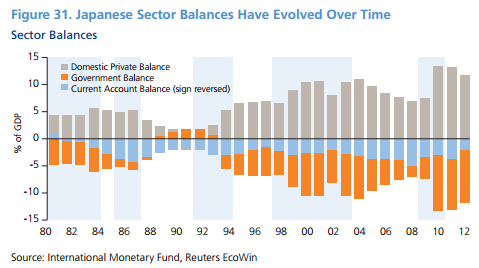

“Understanding sector balances in Japan (as shown in Figure 31 and the accompanying text box) can provide useful insights about the evolution of the Japanese economy. Japan’s domestic sector balance had been weakening in the late 1980s, preceding the bursting of its real estate and equity asset bubbles. Japan has been fairly consistently running current account surpluses over the past three decades, contributing to the surplus of its domestic private balance. However, its general government deficits declined from 1988 to 1991, going from nearly 5% of nominal GDP to a surplus. The decline in the government deficit resulted in the weakening of the surplus in the country’s domestic private balance. In response to slower growth and fiscal stimulus, the surplus in domestic private balances rose in the mid-1990s as the government deficit rose, helping to partly — but slowly — repair the balance sheets of the private sector. Since the mid-1990s, current account balances stayed in the range of around 1.5% to 5.0% of nominal GDP while general government deficits have varied from 2.0% to 10.0% of nominal GDP. Clearly the change in general government deficits has been the main driver in the variation of domestic private balances. As the domestic private sector deleveraged and spurned debt to repair their balance sheets after the bursting of asset bubbles, the government had to run deficits in order to prevent the economy from failing into a tailspin.

Japan’s current account surplus could decline in the coming years, particularly as the country’s export growth slows due to stiff competition from various Asian countries and the strength of the Japanese yen, and as Japan’s energy import bill rises going forward. Remarkably, the Japanese yen had appreciated through the lost decades, thereby limiting the international competitiveness of Japanese exports, while creating deflationary pressures domestically. If in the coming years Japan’s current account surplus diminishes, its government deficits must get larger to retain the domestic private sector’s surplus at its

current ratio.”

Source: ING

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.

Comments are closed.