For many ages to come the old Adam will be so strong in us that everybody will need to do some work if he is to be contented. We shall do more things for ourselves than is usual with the rich to-day, only too glad to have small duties and tasks and routines. But beyond this, we shall endeavour to spread the bread thin on the butter-to make what work there is still to be done to be as widely shared as possible. Three-hour shifts or a fifteen-hour week may put off the problem for a great while. For three hours a day is quite enough to satisfy the old Adam in most of us!²Well, that sure would have been nice. Señor Keynes was off the mark by a wide margin as the average work week in the USA is now 47 hours. What a dope! But maybe it’s not that bad…Maybe Keynes wasn’t as wrong as we might think based just off these rough figures. The main argument against a broad increase in living standards is the idea that real median household incomes have stagnated for much of the last 30 years. This is not true. This myth is usually promoted using this chart:

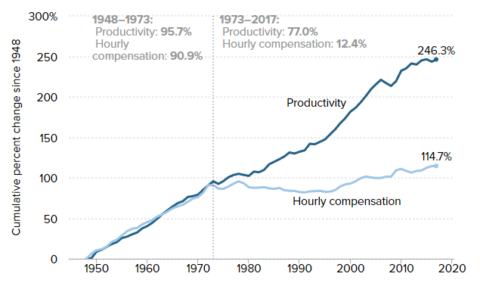

The problem with this chart is that it uses an incorrect price deflator and also doesn’t account for the fact that employees are now compensated largely in benefits. If you use the correct price deflator and broader data you can see that average hourly compensation has actually increased by 65% since 1970. This has been more recently confirmed by Michael Strain’s work, which also shows a more consistent apples to apples comparison between productivity and compensation.

Another common talking point in this debate is that healthcare and college have gotten exorbitantly expensive. That’s largely because we’ve changed our needs and wants over time. 100 years ago you couldn’t dream of going to college or getting modern day medicine. Today we discuss these things as if they’re necessities. In reality, going to college is an enormous privilege. In 1960 just 7.7% of Americans graduated from college. Today just 38% of Americans graduate from college. Getting a college degree is a privilege, not a necessity and certainly not the norm.

Further, the quantity of money we make isn’t necessarily a sign of being better or worse off. Instead, we should look at what those dollars buy and whether they afford us a better use of our time. In other words, do our current incomes give us more freedom to buy the things we want rather than the things we need. By this measure it is irrefutable that American living standards have improved dramatically even during a period when median incomes have stagnated.

A 2003 study from the BLS on American spending trends will help put this in some perspective. In the year 1900 80% of our expenditures went towards necessities (defined as housing, food and apparel by the BLS).³ Over the course of the next 115 years (I updated their study for the most recent data) we’ve seen that share of spending on necessities decline to just 48.9%. Therefore, even though incomes have stagnated for the median income earner that income affords them a higher living standard because it increasingly goes towards inessential spending.

The problem with this chart is that it uses an incorrect price deflator and also doesn’t account for the fact that employees are now compensated largely in benefits. If you use the correct price deflator and broader data you can see that average hourly compensation has actually increased by 65% since 1970. This has been more recently confirmed by Michael Strain’s work, which also shows a more consistent apples to apples comparison between productivity and compensation.

Another common talking point in this debate is that healthcare and college have gotten exorbitantly expensive. That’s largely because we’ve changed our needs and wants over time. 100 years ago you couldn’t dream of going to college or getting modern day medicine. Today we discuss these things as if they’re necessities. In reality, going to college is an enormous privilege. In 1960 just 7.7% of Americans graduated from college. Today just 38% of Americans graduate from college. Getting a college degree is a privilege, not a necessity and certainly not the norm.

Further, the quantity of money we make isn’t necessarily a sign of being better or worse off. Instead, we should look at what those dollars buy and whether they afford us a better use of our time. In other words, do our current incomes give us more freedom to buy the things we want rather than the things we need. By this measure it is irrefutable that American living standards have improved dramatically even during a period when median incomes have stagnated.

A 2003 study from the BLS on American spending trends will help put this in some perspective. In the year 1900 80% of our expenditures went towards necessities (defined as housing, food and apparel by the BLS).³ Over the course of the next 115 years (I updated their study for the most recent data) we’ve seen that share of spending on necessities decline to just 48.9%. Therefore, even though incomes have stagnated for the median income earner that income affords them a higher living standard because it increasingly goes towards inessential spending.

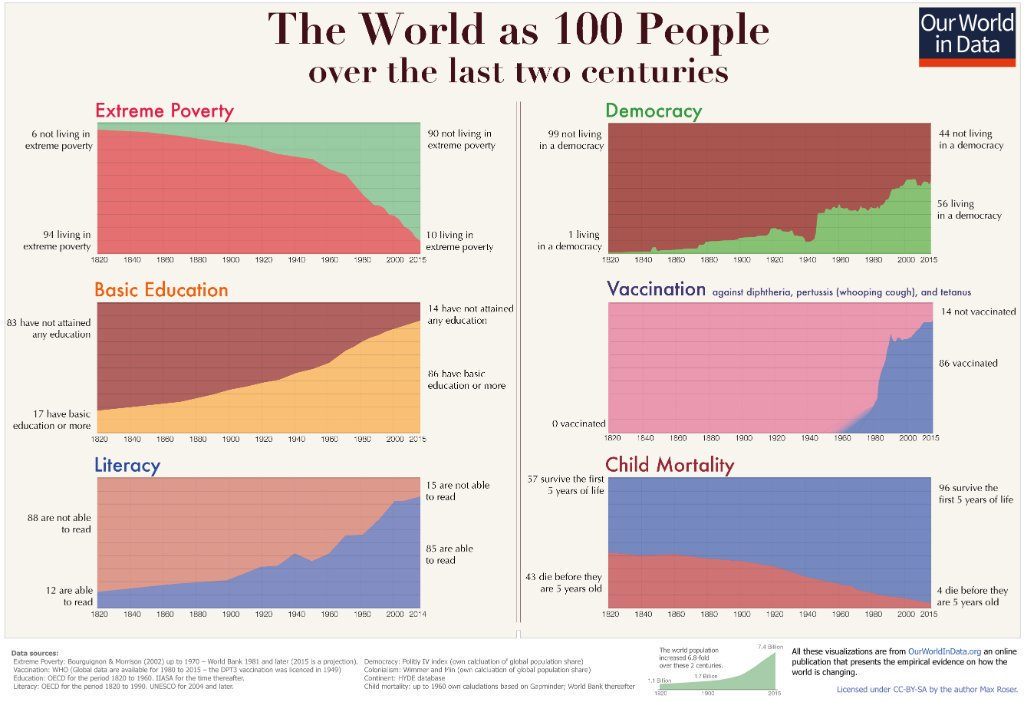

Now, some people might argue that inequality is higher than usual. This is true. But it’s also helpful to keep this in a global perspective. The median American is the global 1%. So, even though inequality is high within the USA the median American is very well off when compared to most other countries in the world.

Of course, none of this means we are doing as well as we could be. I have been highly critical of government policy over the years precisely because I think the US economy is operating at a much lower capacity than it could be. It’s also clear that the growth in living standards has been highly unequal. The upper quintiles of the income range have dramatically improved their position both in real income terms as well as quality of goods and services while the lower quintiles have experienced little to no real income improvement and only improvement in quality of goods and services. So, there are still big problems in the USA. However, I would argue that some of the persistent doom over the current state of the economy is vastly overdone and fails to put the state of American living standards in the proper context.4

Footnotes

¹ – This long-term perspective should be apolitical as it crosses over many political candidates and their policies.

² – See John Maynard Keynes, Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren

³ – See 100 Years of U.S. Consumer Spending. Also, some people might argue that education and healthcare are modern necessities, however, according to the BLS, we spend less on apparel, food, housing, healthcare and education combined in 2015 than we spent on apparel, food and housing in the 1970s. In other words, less of our expenditures are spent on more necessities today. This is a dramatic improvement in living standards.

4 – If this post hasn’t convinced you then I’ll let Louis CK convince you.

NB – Here are some other interesting data points that support this view:

Now, some people might argue that inequality is higher than usual. This is true. But it’s also helpful to keep this in a global perspective. The median American is the global 1%. So, even though inequality is high within the USA the median American is very well off when compared to most other countries in the world.

Of course, none of this means we are doing as well as we could be. I have been highly critical of government policy over the years precisely because I think the US economy is operating at a much lower capacity than it could be. It’s also clear that the growth in living standards has been highly unequal. The upper quintiles of the income range have dramatically improved their position both in real income terms as well as quality of goods and services while the lower quintiles have experienced little to no real income improvement and only improvement in quality of goods and services. So, there are still big problems in the USA. However, I would argue that some of the persistent doom over the current state of the economy is vastly overdone and fails to put the state of American living standards in the proper context.4

Footnotes

¹ – This long-term perspective should be apolitical as it crosses over many political candidates and their policies.

² – See John Maynard Keynes, Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren

³ – See 100 Years of U.S. Consumer Spending. Also, some people might argue that education and healthcare are modern necessities, however, according to the BLS, we spend less on apparel, food, housing, healthcare and education combined in 2015 than we spent on apparel, food and housing in the 1970s. In other words, less of our expenditures are spent on more necessities today. This is a dramatic improvement in living standards.

4 – If this post hasn’t convinced you then I’ll let Louis CK convince you.

NB – Here are some other interesting data points that support this view:

- Household net worth at record highs.¹

- US households spend less on necessities than ever. This “problem” is so bad that the loudest complaints are now about the cost of luxuries like a college education or healthcare.

- Inflation adjusted compensation is up 65% since 1970.

- The misery index is plumbing 60 year lows.

- Real GDP is at all-time highs.

- The rate of change in inflation is close to all-time lows.

- Growth is low, but more stable than ever.

- Global life expectancy is improving dramatically.

- Child mortality has collapsed.

- The world has so much food that we are suffering from an obesity epidemic.

- The cost of that food has collapsed.

- We are experiencing exponential growth in technological advancements.

- The share of the world living in extreme poverty has collapsed.

- Global deaths due to mass conflicts are sharply declining.

- Violent crimes in the USA are near 30 year lows.

- Homicide rates around the world are collapsing.

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.