In aeronautics a “zoom climb” is when an aircraft accelerates at a very high rate of speed and then ascends sharply at a very steep rate. It’s often performed with the aircraft moving at a high rate of speed at a low altitude and then shooting higher in a nearly 90 degree angle. I know nothing about aeronautics, but I know some stuff about money and I am going to explain how this concept can be applied to retirement planning and potential future glide paths. I also think this is a useful concept for understanding why the idea of “your age in bonds” is often wrong.

As I mentioned yesterday, Peter Mallouk sparked a big controversy on Twitter when he said that target date funds are “terrible”. I want to add some more detail here because Peter makes a good point, but I would narrow this criticism more specifically. I think target date funds are generally good, but can be suboptimal in specific circumstances the further you veer from retirement. Generally speaking, target date funds correspond to the “age in bonds” rule.¹ This is the basic thinking that your asset allocation should roughly reflect your age in bonds. So, if you’re 50 years old you should have 50% of your stock/bond mix in bonds. If you’re 25 you should have 25% of your assets in bonds. 75 years old, 75%. You get the picture. I don’t love this rule. Here’s why.

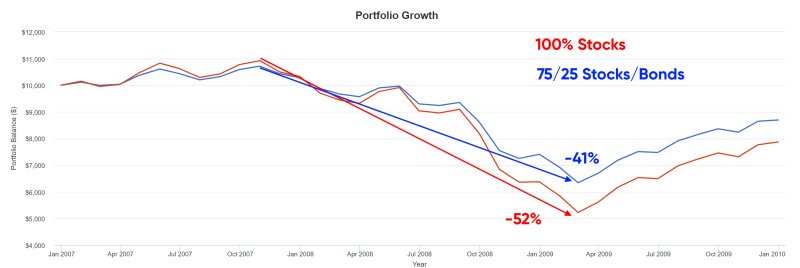

When you’re 25 you probably don’t need a lot of liquidity and you probably have a high risk tolerance because you have a lot of time to sustain drawdowns.² Assuming you have some emergency money and basic spending liquidity you can afford to be very aggressive. More importantly, a 25% bond allocation isn’t doing much for you because the equity piece, at 75% is so much larger that it dominates your portfolio volatility. For instance, during the financial crisis the 75/25 falls 42% while the 100% stock allocation falls 52%. My experience is, when people lose this much money, they are relatively indifferent between these outcomes. Generally speaking, when an investor is down 30% or more they’re scared out of their mind. Being down 40% vs 50% might make someone slightly more comfortable, but both of these investors are extremely uncomfortable. In other words, if you want to hedge such an outcome you need to actually hedge it. Not kinda sorta hedge it.³

Further, the bond allocation is a drag on returns. So, not only is it not providing a good behavioral hedge. It’s just dragging down returns for an investor who should have a very high risk tolerance. This can make a target date fund sub-optimal compared to any strategy that helps the investor stay more aggressive at a time in their life when they can afford to be more aggressive.

The age in bonds rule has the same sub-optimal type of outcome later in someone’s life. As you near 80 years old, for instance, your risk profile is likely getting more aggressive because the assets in your portfolio likely aren’t yours. They’re likely to be inherited. This means that the assets have a longer asset-liability matching period than they did, for instance, when you were 65 and the funds were more likely to be yours.

In addition, I’d argue that there are very few people who shouldn’t own at least a 25% chunk of stocks. Using the same risk-parity style thinking as above, the equity slice of a 25/75 stock/bond portfolio is very well hedged by the bond component even though the 25% slice is so much more volatile than the bonds. There’s no need to be 80/90/100% bonds in most cases because then you’ve skewed everything too far in the opposite direction where you’re generating very low returns and not hedging against inflation.

All of this is compounded in a low interest rate environment where bonds cannot generate returns that, on their own, meet withdrawal rates and income needs. This can compound the management of withdrawal rates, which, as Andrew Miller notes, can be exacerbated in a target date fund approach.

It’s Time to Zoom

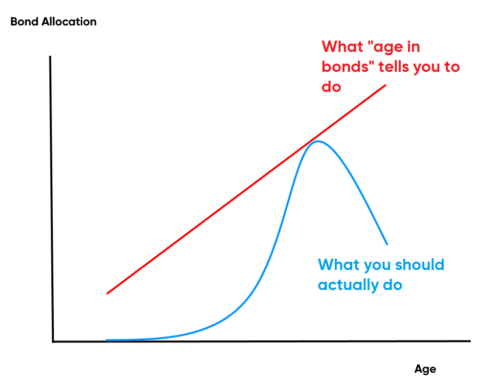

A potential alternative rule of thumb is to apply this zoom climb concept to the bond allocation because the liquidity needs of an investor are generally very well defined around your retirement  years. The image below shows a comparison of a zoom climb approach vs age in bonds. The age in bonds rule starts with a sub-optimal bond allocation and becomes increasingly appropriate as you near retirement. But then it continues on this same trajectory resulting in an excessive bond allocation as time goes on. Instead of this approach most investors should construct a specific time horizon over which their uncertainty of liquidity needs is greatest. This is what Michael Kitces refers to as the “retirement red zone”. As a general rule, this period of uncertainty is likely to center around your retirement years when your income will decline and you will start taking portfolio withdrawals.

years. The image below shows a comparison of a zoom climb approach vs age in bonds. The age in bonds rule starts with a sub-optimal bond allocation and becomes increasingly appropriate as you near retirement. But then it continues on this same trajectory resulting in an excessive bond allocation as time goes on. Instead of this approach most investors should construct a specific time horizon over which their uncertainty of liquidity needs is greatest. This is what Michael Kitces refers to as the “retirement red zone”. As a general rule, this period of uncertainty is likely to center around your retirement years when your income will decline and you will start taking portfolio withdrawals.

The big behavioral problem around retirement is that your job and income operate a lot like a fixed income position. That is, you have this asset that kicks off consistent income. This makes your financial planning needs very predictable as you can match your expenses with your income. Retirement is difficult because this asset disappears. You lose substantial income yet you want to maintain the same general standard of living that you’ve become accustomed to. And while you might have a portfolio of assets that can offset this lost employment asset there is increased uncertainty around how to manage your liabilities. This is why an increased bond and income position around retirement can help offset the behavioral hurdles around lost income in retirement.

The zoom climb concept is similar to what Kitces has referred to as a “bond tent” approach to retirement planning. In essence, the goal is to create a shelter of protection that increases portfolio certainty during the specific period in your life when uncertainty will be at its greatest. Importantly, it increases average risk across time by being more aggressive during the periods when you likely don’t need as much near-term certainty. This should boost total returns on average and increase positive outcome probabilities of retirement funding needs.

In sum, target date funds do a lot of great things. Low fees, diversification, simplicity, etc. These are all wonderful features and you could do much worse than that. These funds could be useful if they’re utilized directly within the retirement planning window. However, they become particularly counterproductive for people outside of this window and the inefficiencies compound the further outside the window you get. This is why it might be wise to consider a more flexible approach to asset allocation when considering how you’ll apply your personalized asset allocation.

¹ – I am generalizing here. Many target date funds are more dynamic and have stricter operating rules than this.

² – I am taking a good deal of liberty with the assumptions here. Everyone is different, yada yada yada.

³ – This whole concept is kind of like buying term life insurance. That basic thinking applies here in the sense that you’re buying bonds for a specific term of your retirement when uncertainty is highest. You don’t need portfolio insurance for your whole life. You need it most in a specific window in most cases.

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.