Here’s a great question from Joe Weisenthal’s morning update:

I’ve spilled a lot of ink over the last decade talking about debt, deficits and sectoral balances. My broader points have been largely proven right over that time:

- The US government does not operate like a household or business and operates with an inflation or currency constraint and not a traditional solvency constraint.

- The US government was never at risk of a solvency crisis and its bonds were never at risk of default.

- Government debt bolstered private sector balance sheets during the financial crisis and the deflationary bust and never posed a risk of hyperinflation.

- US government debt does not compete with private sector debt in a loanable funds model and therefore never posed a risk of causing high interest rates.

There are a lot of moving parts in this discussion so we should be careful about generalizing. But I’ll try to keep this relatively simple.

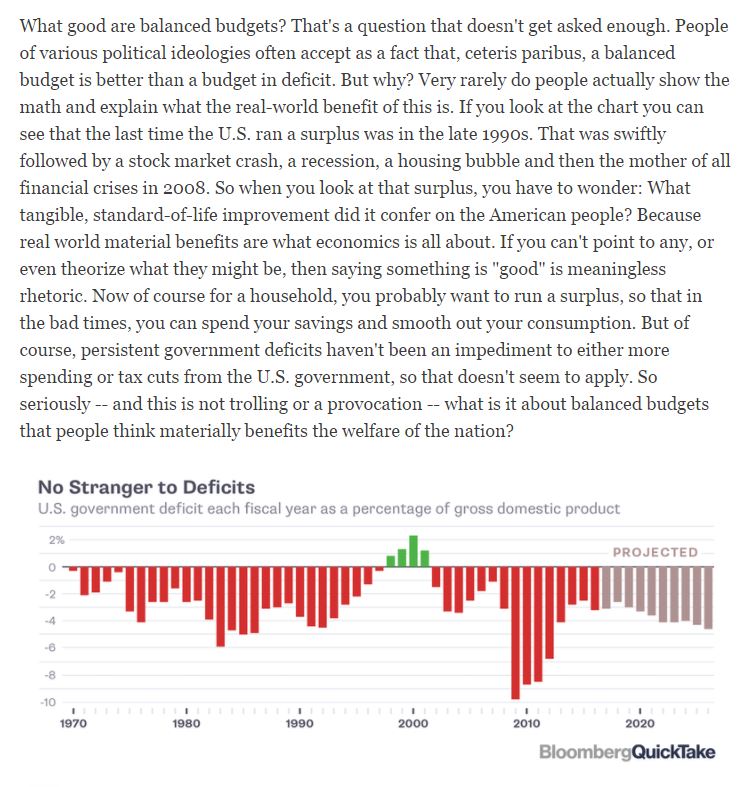

Balanced budgets are attractive for an obvious reason – they imply fiscal responsibility. Running a persistent deficit implies fiscal irresponsibility. Of course, life is more complex than that. For instance, at the aggregate global level all balance sheets balance. Balanced budgets are the natural state of being. But we’re necessarily talking about a more micro case of governments and households so let’s dive deeper.

First of all, US households are always in debt and increasingly so. This does not mean US households have always been irresponsible. In fact, household net worth tends to increase over time in large part because debt is being used to create equity which strengthens our balance sheet. Said differently, debt can be used to create assets that become more valuable over time. This is a very good thing and it would be self defeating if we said households should always be fiscally responsible and balance their budgets. In fact, we want households and businesses to be responsibly irresponsible so that they take risks on innovations and products that improve our living standards and the health of our balance sheets.¹

But what about governments? Is a balanced budget good or bad? It really depends on the specifics of the environment. Just like US households, the government is just about always taking on more debt and like private sector borrowing this is not always necessarily productive or adding to our long-term well-being. So again, we have to be careful about generalizing. I mean, I think we can all agree that a government in a hyperinflation will not solve its inflation by spending money recklessly.

Anyhow, I think the relevant question to answer here is whether the government’s deficit or surplus position is contributing positively to the environment in which the private sector can increase the health of its balance sheet by innovating, producing and building equity. This is an exceedingly complex point to prove or disprove, but here are a few things I think we can reasonably agree on:

- Governments issue assets/liabilities that are of inherently high credit quality because they are backed by the ability to tax a productive private sector. They are the inherently low risk financial assets/liabilities because of this aggregated taxing power.

- Because governments are not prone to solvency crises in the same sense that a household is, they can operate in a more flexible manner that counteracts private sector strength or weakness during times of economic boom/bust. Because of its unique ability to spend without worry of profit the government can act as a spender/lender of last resort during times when the economy freezes or slows. Likewise, it can close the spending valve when the economy is operating above capacity because it does not rely on the income to remain solvent.²

So, as a starting point we should all agree that it can be good for a government to issue some level of liabilities because they serve as inherently risk free assets that can serve as natural foundational components of a healthy private sector balance sheet. Holding AAA rated US government bonds in my portfolio allows me to operate with a higher degree of certainty than holding AA rated corporate bonds. In addition, we should all agree that it can be a good thing for the government to operate its balance sheet in a countercyclical fashion that naturally offsets the boom/bust tendencies of the private sector. That is, when the economy is booming it can be good for the government to be more constrained and try to halt the excesses of the private sector (this does not always work as the late 90’s show). And when the economy is busting it can be good for the government to operate as a spender/lender of last resort to try to restore some semblance of normalcy to an economy that is faltering.

That second point is of particular importance here. Many people blame President Obama for the surge in debt and the deficit. But this was not his doing. The deficit and debt surged because tax revenues collapsed and automatic stabilizers (like unemployment benefits) surged. Our deficit expands and contracts across time in a natural manner that responds to the state of the economy. Ie, the deficit in 2009-2016 increased automatically. And this was a good thing as it provided income and assets to the non-government sector when non-government incomes and assets were deteriorating. The opposite occurred during the Clinton boom. Bill Clinton did not create the surplus any more so than Obama created the deficit. But politically motivated people often infer cause and effect in order to promote a certain political agenda when the reality is that the economy is much bigger than Washington DC and its antics. The key point is that the deficit is largely an ex-post effect of other things occurring in the economy.

I still haven’t answered the real question though. Are balanced budgets good or bad? Well, it depends. But let’s run through a simple thought experiment. Let’s say we have a highly productive and stable private sector worth $100 and growing at 1% per year. If the government currently has a national debt of $10 (that’s $10 worth of assets for the private sector) and decides to run a $1 surplus every year then they are retiring $1 worth of debt each year. Now, remember point 1 above. Those government bonds are equivalent to the quality of the aggregate private sector income stream because they are a function of the strength of the private sector. As a result they MUST be an inherently higher quality asset. So, at the end of 10 years we will have no government debt and an economy that has grown to be worth $110.46. This seems great, except for one point. Our balance sheet has grown and appears healthy, but it MUST, by definition, be a lower quality balance sheet. That is, it is now comprised entirely of AA rated instruments whereas it was before bolstered by 10% AAA rated instruments.

But here’s the kicker – if balance sheet expansion is good and necessary then why would we operate our government in a manner that inhibits private sector risk taking by making our balance sheet lower quality and more fragile than it otherwise could be? In other words, if we can run a reasonably small deficit in perpetuity and this deficit adds to the certainty and credit quality of our aggregate balance sheet thereby allowing risk takers to do what they do best (take risks) then isn’t this a no-brainer way to operate the government’s balance sheet?

So, I guess I would throw the question back to the debt boogeymen – given that the US government doesn’t have a solvency constraint like a household or business and can provide safe balance sheet bolstering assets in near perpetuity (assuming we have a healthy productive private sector³), why do we feel the persistent need to run a balanced budget or surplus?

¹ – People should really stop with the dangerous generalization that debt is always bad. Debt reflects the expansion of a balance sheet wherein two parties obtain offsetting assets and liabilities. Whether this balance sheet expansion is good or bad is a function of whether the borrowing party can sustain this debt position which is a function of how that debt is used. Debt, in this sense, is like a drug. It is neither inherently good nor inherently bad, but can be used for good and for bad. When used for good it is not just a net benefit to the economy, but an essential component of sustainable growth.

² – I should note that government debt and spending can be a slippery slope. In moderation some degree of government debt is probably good and totally sustainable when accompanied by a productive private sector. However, a government that disincentivizes its private sector from being productive will obviously create an environment ripe for inflation and a devalued currency as that currency becomes less valuable relative to the productive goods and services it can purchase.

³ – Having such an extraordinarily productive private sector is an exorbitant privilege that provides the US with a greater scope of policy flexibility. As I’ve said in the past, capitalism makes socialism sustainable and no one does capitalism better than the USA. So it begs the question, why would the wealthiest society in the history of mankind convince itself that it cannot afford some modest degree of government deficit?

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.