As a general rule I like simple indexing strategies like a 60/40 stock/bond portfolio, for the right person. It’s perfectly consistent with what I would call a “discipline based investing” strategy in that it’s evidence based, low cost, tax efficient, systematic and helps to self regulate behavior by rebalancing back to a less procyclical stock weighting over time. In other words, if you didn’t rebalance your 60/40 then it would grow to 70/30 (or more stocks) over time and this would create an imbalance between your risk profile and your allocation. Rebalancing back to 60% stocks helps regulate that skew and reduces the downside variance if the stock market falls a lot. We call a portfolio like 60/40 a “balanced” index, but is it actually balanced? I don’t think so and I think this is a big problem for a lot of investors.

Years like 2022 expose an uncomfortable and important truth about this “balanced” allocation – it’s not actually balanced at all. For instance, the stock market is down 22% as I type. And the bond market is down 11% as I type. Bear in mind, that 11% downturn for bonds is enormous. It’s about as bad as it gets for bonds. And they’re still down HALF of what the stock market is. On the other hand, we know that a bad stock bear market is often -30%, -40% or -50%. The key point is that our 60/40 portfolio has a -17.6% return this year, but SEVENTY FIVE PERCENT of that downside is coming from the 60% slice. This isn’t “balanced” by any means. And to make matters worse, we know that the stock piece often becomes riskier during big booms. High valuations tend to result in lower long-term average returns. This means that if you rebalanced to 60% at the end of 2021 you not only rebalanced back to a fixed weighting that was unbalanced relative to the bond allocation, but you also rebalanced back to a weighting that was cyclically riskier because that 60% slice you started with in 2021 is different from the 60% slice you ended the year with!

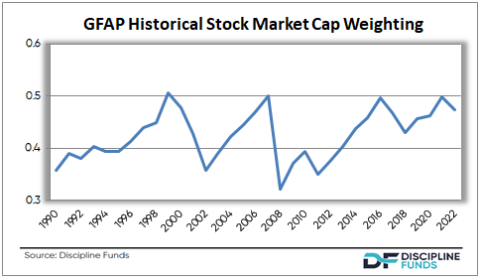

The even more interesting aspect in all of this is that we know the market cap weightings of the underlying markets are hugely dynamic. For instance, here’s the stock market capitalization over the last 30 years. It gyrates between 35% and 50% with regularity, but the interesting thing to note is that it tends to boom towards the 50% when stocks are overvalued and collapses back to 35% when stocks are undervalued. So, if you’re rebalancing back to 60% stocks every year you’re not only rebalancing back to an unbalanced nominal position, but you’re rebalancing back to a position that, in cyclical terms, becomes riskier when the Global Financial Asset Portfolio (the GFAP, the market cap weight of all the world’s outstanding financial assets) allocation grows. This means your 60% slice is riskier during the booms and exposes you to the exact kind of behavioral risks we tend to see in years like this.

between 35% and 50% with regularity, but the interesting thing to note is that it tends to boom towards the 50% when stocks are overvalued and collapses back to 35% when stocks are undervalued. So, if you’re rebalancing back to 60% stocks every year you’re not only rebalancing back to an unbalanced nominal position, but you’re rebalancing back to a position that, in cyclical terms, becomes riskier when the Global Financial Asset Portfolio (the GFAP, the market cap weight of all the world’s outstanding financial assets) allocation grows. This means your 60% slice is riskier during the booms and exposes you to the exact kind of behavioral risks we tend to see in years like this.

It all begs the question – why do index funds rebalance back to fixed weightings when we know that the underlying market caps are dynamic? We know the actual underlying market cap is floating and changing all the time yet we rebalance back to fixed weights. This doesn’t make sense! Why wouldn’t we try to create more balance in these indices across time so that the actual portfolios are more consistent not only with the underlying GFAP changes, but also the way investors actually perceive risk? Sure, I love the simplicity of a fixed weight index fund, but in today’s world of low cost indexing it’s so easy to create floating benchmarks that actually track the markets. If this is more consistent with “balanced” indexing and a true passive cap weight then why aren’t the big indexing firms already doing this?

Of course, I am talking my book because that’s exactly what Countercyclical Rebalancing is all about – overbalancing at times to create a portfolio that is more consistent with how we actually perceive risk. And that’s what Discipline Funds is implementing. But this all seems like such an obvious fact of financial markets that it really begs the question – why aren’t we building actual “balanced” index funds already? Or more interestingly, why do we call things “balanced” when in fact we know they’re not?

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.