In a recent story I pointed out that Richard Koo said it was not significant that the USA has been faster to respond to the current balance sheet recession. Now, he was primarily referring to the ineffectiveness of monetary policy during a balance sheet recession and the fact that it doesn’t matter how quickly you cut rates or implement QE during this sort of recession. I largely agree with these comments. But I think it’s important to note that the USA has a slightly different form of balance sheet recession and is responding to it with fiscal stimulus more quickly than the Japanese did. This, in my opinion, is unlikely to result in a balance sheet recession as long as Japan’s.

Just to review – it’s important to note that Japan’s debt crisis existed primarily at the corporate level. In his superb book, The Holy Grail of Macroeconomics, Koo explained the situation:

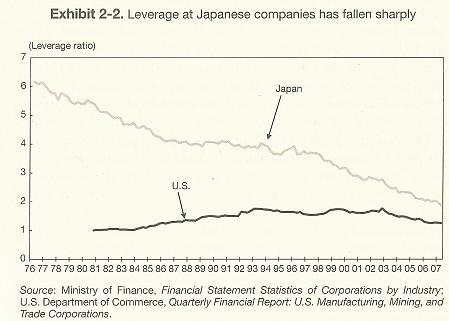

“Indeed, this leverage issue was another reason Japanese firms moved to pay down debt during the 1990s. Exhibit 2-2 shows leverage ratios at Japanese and US firms. Japanese businesses used to be extremely dependent on debt financing relative to their Western counterparts. In the first half of the 1980s, for example, leverage ratios at Japanese firms were five times those at US corporations. But no one thought twice about this at the time, because the economy was rapidly expanding, and asset prices were surging higher. Few were worried about debt levels under these circumstances. After all, the use of borrowed money to acquire assets raises few eyebrows as long as the economy is expanding and the value of corporate assets is rising. If anything, companies were commended for taking on more debt because greater leverage translated to a higher return on equity.

But this cycle began to reverse when the bubble burst in 1990, and the Japanese economy entered a period of low growth and falling asset prices. Companies carrying heavy debt loads still had to service this debt even as earnings declined, putting their survival in jeopardy. In effect, firms had to pay down debt starting in 1990 not only to put their balance sheets in order, but also to bring leverage down to a level benefitting an era of lower growth. In this sense, too, Japanese firms have made substantial progress in reducing leverage over the past 15 years.”

These are very important points. You could essentially replace “households” with “businesses” in the above paragraph and you’d be describing the situation in America today. And that’s the exact difference. Our balance sheet recession is a household debt crisis whereas Japan’s was a corporate debt crisis. As I’ve often said over the years, effective policy needs to focus on households and not banks. This was always a household debt crisis and not a banking crisis. And while America’s banks are still distressed (although they’re in far better condition than they were in 2008), American businesses are actually very healthy today and I think that is proving to cushion the downside during this recession.

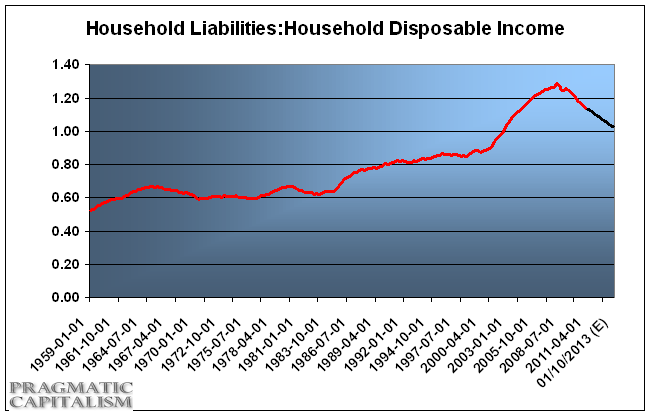

As you can see from the above chart Japanese businesses were grossly overleveraged. And while US households suffered a massive bubble the leverage was nowhere near the same levels. If we look at household liabilities to disposable income we can see that the problem is by no means good, but it is becoming more stable by the day:

This is a large part of my estimate for 2013/14 being the end of the balance sheet recession. Given recent trends, the cash flows of households should begin to support organic recovery long before the de-leveraging was done in Japan. While we are likely to suffer several more years of weak growth we don’t yet need to fear another lost decade.

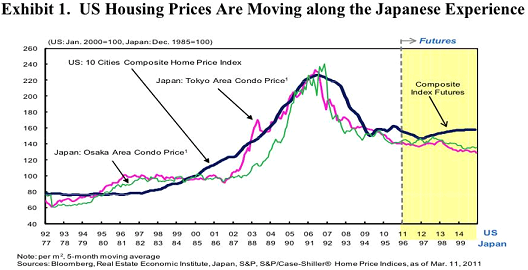

Further supporting this theory of a shorter balance sheet recession is US house prices. Richard Koo notes that Japanese corporations were struck by declining asset prices. The fact that they had an equity AND housing bubble at the same time served as a double whammy in this regard. The USA, on the other hand, suffered the equity market bubble more than 10 years ago. So the impact in recent years has been more concentrated on the collapse in real estate prices. As I’ve previously noted, I think the majority of the price declines are behind us in housing. This is confirmed by price trends in Japan as well (see below). This should stop the uncontrolled bleeding that has caused so much imbalance in recent years.

Lastly, the USA was faster to implement the all important fiscal policy that Richard Koo prescribes. Contrary to political fearmongering and claims that fiscal stimulus has destroyed jobs, the CBO and the sectoral balances prove that fiscal stimulus has aided in helping the household sector during this de-leveraging (common sense is all it should really take to understand this, but politics and confirmation bias cloud people’s judgment). This “recovery” has been largely stimulus driven. It has not been organic by any means, but that is the nature of the balance sheet recession. If government doesn’t fill the spending void, the bad decisions of the few who caused the debt bubble end up causing the rest of us to suffer a depression alongside them.

In the USA President Bush actually initiated fiscal stimulus before the crisis really hit. In February 2008 he implemented the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008. This was obviously not that effective, but was followed up by the massive stimulus package after the collapse (please see the bipartisan CBO’s details on the effects of the stimulus). The Japanese, on the other hand, did not implement fiscal policy until almost three years into their crisis. Over the ensuing 6 years Japanese stimulus was a stop and start process with political bickering inbetween (which is beginning to ring all too familiar as our politicians bicker over the debt ceiling).

Most importantly, we have not allowed ourselves to be talked off the edge of the cliff by those who fear the USA is going bankrupt. Unfortunately, the risk of fiscal austerity poses a serious threat to my optimistic end date for the balance sheet recession. I am probably naively hopeful that austerity turns out to be less negative than some currently think, but I do acknowledge that this is an enormous downside risk. As Warren likes to say, “because we think we are the next Greece, we are becoming the next Japan”. I sure hope not.

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.

Comments are closed.